Assessing monitoring and alerting policies

As we covered in Chapter 7, Tools for Monitoring and Assessing, cloud monitoring is a method of reviewing, observing, and managing the health and security of a cloud. Using monitoring tools, organizations can proactively monitor their cloud environments to identify issues before they become security risks. AWS, Azure, and GCP offer native solutions that an IT auditor can leverage to monitor and assess cloud environments. Let us start by looking at AWS.

AWS

The first monitoring tool an IT auditor can leverage in AWS is Amazon CloudWatch.

Amazon CloudWatch

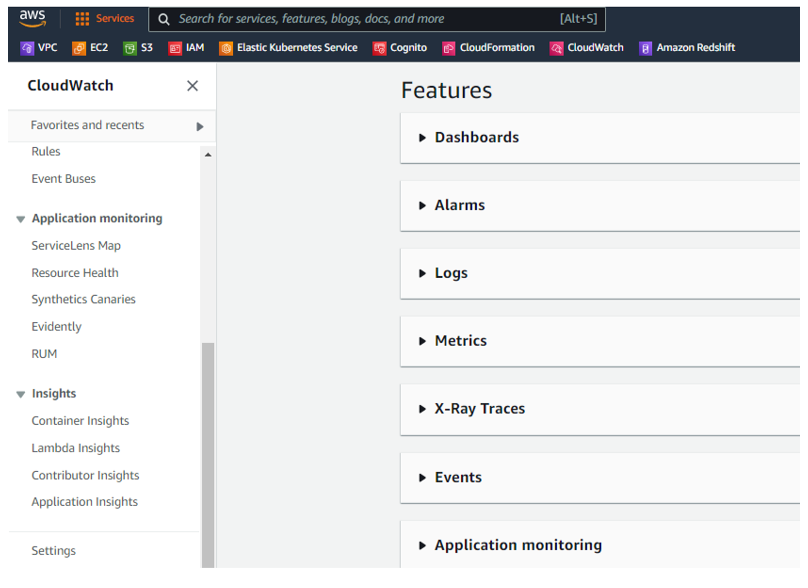

Amazon CloudWatch is an AWS native monitoring and management service that is designed for the purpose of monitoring the services and resources that are used. Amazon CloudWatch can be used to collect and track metrics, monitor log files, and set alarms, among many other functions. To review these findings, we will need to perform the following steps to launch Amazon CloudWatch, as seen in Figure 10.24:

- Navigate to the AWS Management Console.

- Select CloudWatch | Dashboards.

Figure 10.24 – Amazon CloudWatch

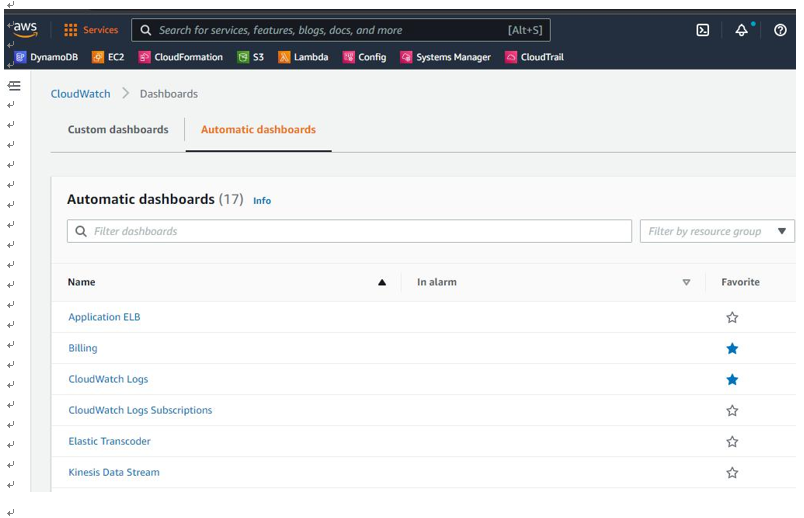

Under Dashboards, an IT auditor can create custom dashboards. Under Automatic dashboards, you can pick further options. In this scenario, we have picked Billing and CloudWatch Logs to add to our custom packtestdashboard dashboard, as seen in Figure 10.25:

Figure 10.25 – CloudWatch | Dashboards

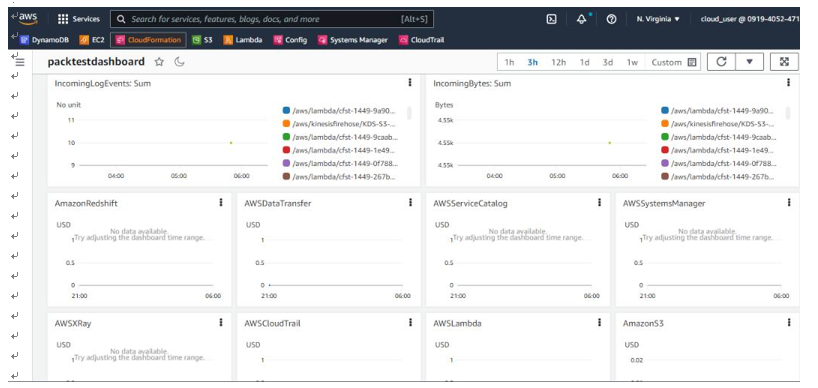

You can see the dashboard displays billing information for different services as well as CloudWatch logs, as seen in Figure 10.26:

Figure 10.26 – CloudWatch | packtestdashboard

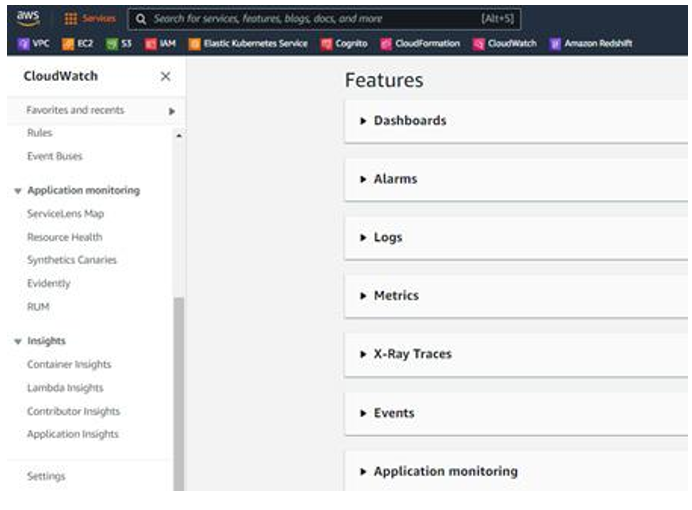

Amazon CloudWatch also has a feature named CloudWatch Alarms that an IT auditor can leverage. CloudWatch Alarms has the functionality to monitor defined metric changes that have crossed a specified threshold. To launch Alarms within Amazon CloudWatch, as seen in Figure 10.27, perform the following steps:

- Navigate to the AWS Management Console.

- Select CloudWatch | Alarms.

Figure 10.27 – CloudWatch | Alarms

An IT auditor can create an alarm that triggers when a certain metric changes. I will provide examples of two rules an IT auditor can create.

Note

For detailed instructions on creating CloudWatch alarms, go to:

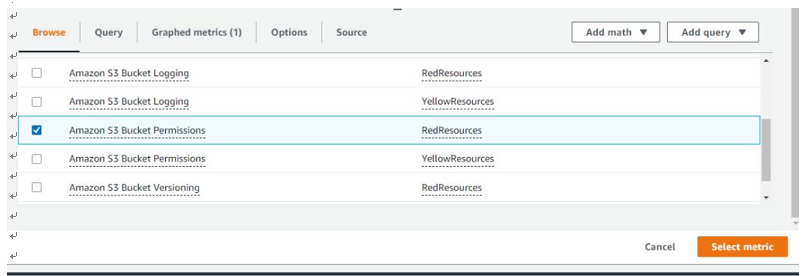

In our first example, we select a metric that triggers an alarm when an AWS Simple Storage Service (S3) bucket permission changes, as seen in Figure 10.28. An IT auditor could use this rule to monitor changes in S3 buckets. They could also use this rule to look for misconfigured S3 buckets that allow public access. This is one of the most common security misconfiguration risks within AWS.

Figure 10.28 – Amazon S3 Bucket Permissions metric

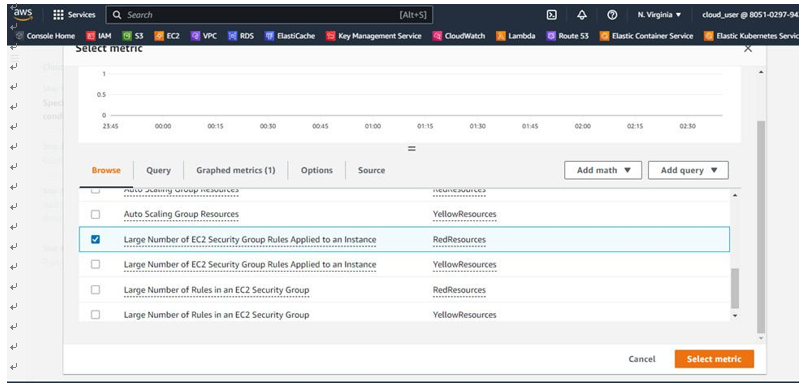

In our second example, we can select the Large Number of EC2 Security Group Rules Applied to an Instance metric to trigger an alarm, as seen in Figure 10.29:

Figure 10.29 – The Large Number of EC2 Security Group Rules Applied to an Instance metric An IT auditor could use this rule to monitor for malicious activity or insider threat activity where a user would add security groups to an EC2 instance, bypassing the regular process.

Now that we have looked at monitoring tools in AWS, let us look at tools we can leverage in Azure.

Azure

One of the tools an IT auditor can leverage for monitoring in Azure is Azure Monitor.

Azure Monitor

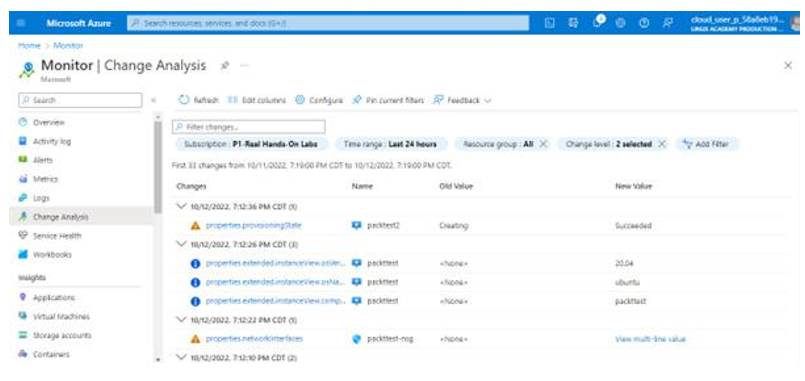

As we mentioned earlier, Azure Monitor aggregates and correlates data across Azure cloud resources. Within Azure Monitor, there is a useful feature named Change Analysis. Change Analysis detects and helps monitor various types of changes, from the infrastructure layer through application deployment, as seen in Figure 10.30:

To launch Change Analysis within Azure Monitor, perform the following steps:

- Navigate to the Microsoft Azure portal.

- Select Monitor | Change Analysis.

Figure 10.30 – Azure Monitor | Change Analysis

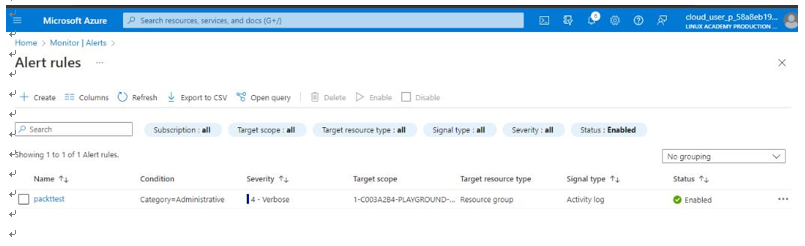

Azure Monitor also has the ability to trigger alerts. This can be done through the configuration of alert rules. Perform the following steps to launch Alerts within Azure Monitor, as seen in Figure 10.31:

- Navigate to the Microsoft Azure portal.

- Select Monitor | Alerts.

An IT auditor can set up alerts for various conditions. In this example, we are setting up alerts for All Administrative Operations over the last week, as seen in Figure 10.31:

Figure 10.31 – Azure Monitor | Alert rules

This type of rulecan be useful to an IT auditor to monitor administrative operations and ensure they are authorized.

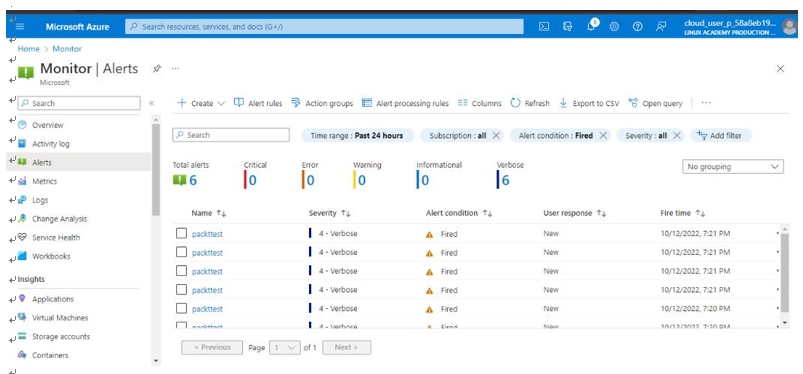

For illustration, we went ahead and performed some administrative operations. The alerts were triggered, as seen in Figure 10.32. The IT auditor can perform further investigations on the alerts:

Figure 10.32 – Azure Monitor | Alerts

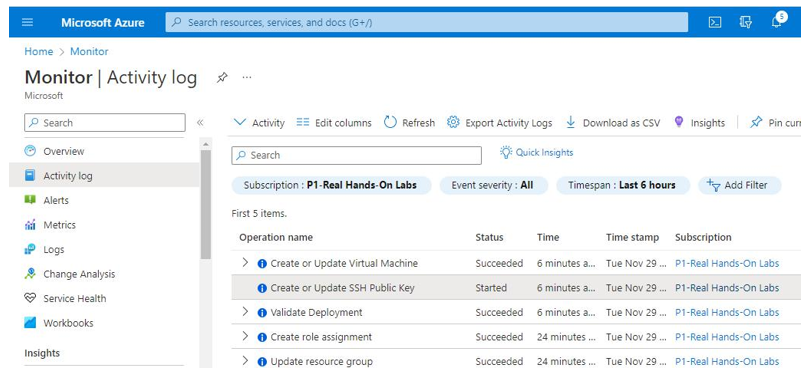

In addition, an IT auditor can create an activity log alert rule from the Activity log plane. The Activity log plane contains information about Azure resource changes. Use the following steps to launch Activity log within Azure Monitor, as seen in Figure 10.33:

- Navigate to the Microsoft Azure portal.

- Select Monitor | Activity log.

Figure 10.33 – Azure Monitor | Activity log

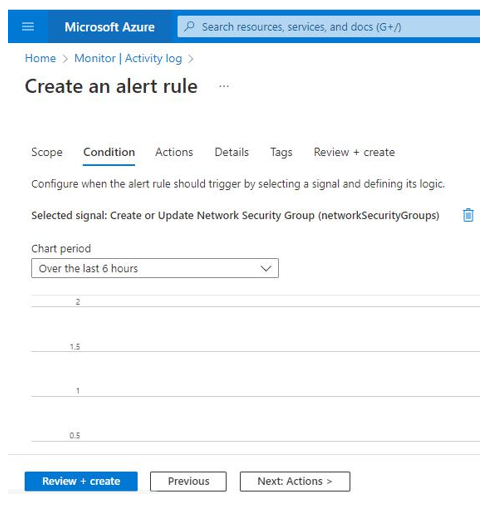

To create an alert, select any activity within Activity log. In this example, I selected one of the events,

Create or Update Network Security Group, as seen in Figure 10.34:

Figure 10.34 – Alert Rule: Create or Update Network Security Group

Now that we have looked at monitoring tools in Azure, let us look at tools we can leverage in GCP.