Where are the boundaries of SaaS?

We’ve laid a foundation here for what it means to be SaaS, but there are lots of nuances that we haven’t really talked about. For example, suppose your SaaS application requires portions of the system to be deployed in some external location. Or, imagine scenarios where your application has dependencies on other vendor’s solutions. Maybe you are using a third-party billing system or your data must reside in another environment. There are any number of different reasons why you may need to have parts of your overall SaaS environment hosted somewhere that may not be entirely under your control.

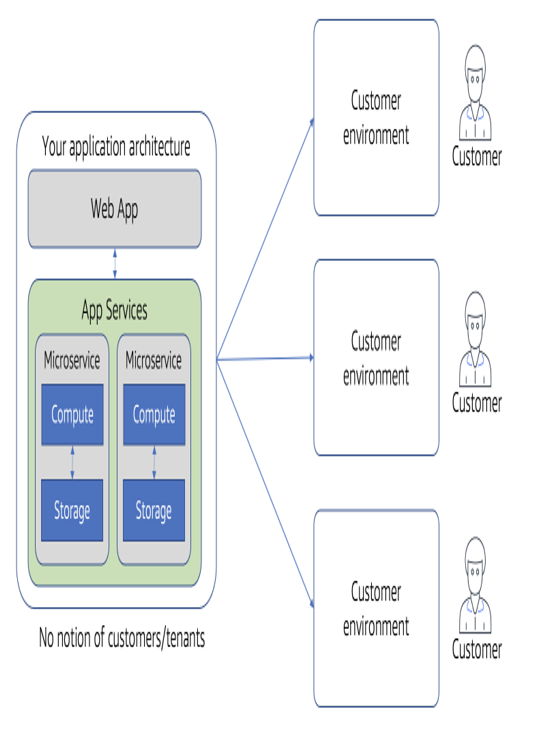

So, how would this more distributed footprint fit with the idea of having a single, unified experience for all of your tenants? Afterall, having full control over all the moving parts of your system certainly maximizes your ability to innovate and move quickly. At the same time, it’s impractical to think that some SaaS providers won’t face domain and technology realities that require them to support externally hosted components/tools/technologies.

This is where we don’t want to be too extreme with our definition of SaaS. To me, the boundary is more around how these external dependencies are configured, managed, and operated. If their presence is entirely hidden from your tenants and they are still managed and operated through your centralized experience, this is still SaaS to me. It may introduce new complexities, but it doesn’t change the spirit of the SaaS model we’re trying to build.

Where this gets more interesting is when SaaS providers have reliance on external resources that are in the direct view of their tenants. If, for example, my SaaS solution stores data in some tenant-hosted database, that’s where things get more dicey. Now, you may have a dependency on infrastructure that is not entirely under your control. Updating this database, changing its schema, managing its health–these get more complicated in this model. This is where we start to ask questions about whether this external resource is breaking the third-wall of SaaS, exposing tenants to infrastructure and creating expectations/dependencies that undermine the agility, operations, and innovation of your SaaS environment.

My general rule of thumb here (with some exceptions) is that we’re providing a service experience. In a service model, our tenant’s view is limited to the surface of our service. The tools, technologies, and resources that are used to bring that service to life should be entirely hidden from our tenants. In many respects, this is the hard barrier that prevents our system from falling back into patterns that might lead to one-off dependencies and variations.